The 2000's Trend

- lukecyrus

- Sep 18, 2023

- 4 min read

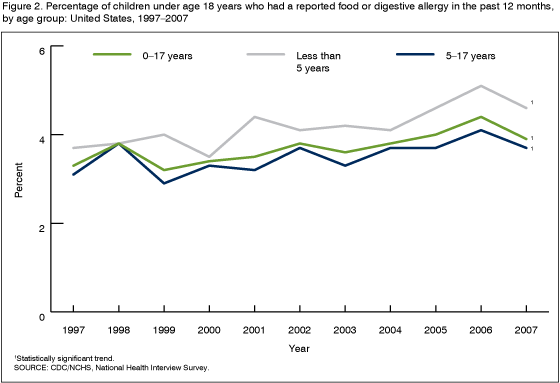

This post is more of an allergy-science post than advocacy. I felt the need to write about this because I've been asked many times why my generation saw such a spike in food allergy prevalence. The honest answer is nobody knows for certain. However, any inferences that are to be made must be based off of observable population trends. For starters, lets take a look at this graph released by the CDC regarding this issue, just to establish a precedent here:

We can see that the demographic that saw the highest spike in the decade depicted was the age group from 0-5, which is consistent with both anecdotal testament across the nation, as well as clinician reports during this time. According to the actual study (cited at end of article), in 2007, approximately 3 million children under age 18 years (3.9%) were reported to have a food or digestive allergy in the months leading up to the data accumulation. Its also worth noting that, generally, after the year 2000, the prevalence rates across all 3 groups started to significantly rise. The question is why is that?

Several aspects have been considered, including the following in that same study:

With regards to the influence of gender (if any), it was a roughly even distribution of frequency, with the female group marginally edging out the male group. For the ethnicity groups polled, one serious limitation is that its scope was restricted to only White, Black, and Hispanic demographics, however, with the data available, we can see that the disease affects a wider range of populations amongst the Black and White ethnicity groups in America. At the time though, this was one of the few credible resources available to clinicians and researchers to interpret the frequency implications of allergies at large. However, no meaningful causal links were established in that study. For that to surface, more time has to pass before this irregularity can be sorted out to some degree.

Here's a deeper look into the trends during the 2000s. By far, the most notable influencer of the rising prevalence rates during this time remains the phenomenon I have informally termed as the "90's scare". In short, during the 90's, prevalence rates began to rise, and doctors in turn prescribed treatment largely revolving around abstinence. That is, 100% avoidance of a patient's allergens in the hopes that the immune system's hypersensitivities would eventually fade out with age. However, what ended up happening instead was that the prevalence rates soared in the years that followed this age of science. Clearly, this approach was not working.

With this development in the patient population, an evolving response in turn was forming. Rather than avoidance driving waning hypersensitivity, medical professionals started to approach the problem from the opposite extreme on the treatment spectrum. Researchers and doctors started to experiment with the notion that micro exposure over time could build tolerance to allergens in large doses. They implemented several techniques over the course of the years that followed, including immunotherapy and food challenges. This gave rise to the widespread use of what is now known as AIT: Allergy Immunotherapy.

The American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology defines AIT as being "a preventive treatment for allergic reactions... (it) involves giving gradually increasing doses of the substance, or allergen, to which the person is allergic. The incremental increases of the allergen cause the immune system to become less sensitive to the substance, probably by causing production of a “blocking” antibody, which reduces the symptoms of allergy when the substance is encountered in the future. Immunotherapy also reduces the inflammation that characterizes rhinitis and asthma." This is a very technical explanation which I will cover in another article, but essentially, this technique successfully built resistance against allergen exposure amongst the patient body in the

United States. How successful was this new approach?

Quite impressive.

In this longitudinal study, for example, roughly 46,000 test group members were evaluated in performance against control subjects form a control group of similar proportion containing patients with allergies who were on non-AIT medications (Rx) to deal with the chronic issue. In terms of prescriptions given for treatment, what is seen is that over time, the AIT (allergy immunotherapy) group's frequency of reliance on immunity related allergy-related prescriptions decreased at a faster rate than that of the control's which indicated that the AIT was reliably working over the course of 9 years of study, essentially weaning them off of their other suppressants, evidencing resistance! And this is just one of many studies that evaluates this phenomenon.

Today, more expansive data about prevalence rates exists. Here is amore recent graph of more inclusive sample sets published as "Food Allergy Perceptions and Health-Related Quality of Life in a Racially Diverse Sample" (cited at bottom):

We see that now, rates in the Asian American demographic have come to rival the highest numbers that were seen in the CDC's previous foundational study. Unfortunately, its too early to tell the national scale of impact that AIT has had on the massive patient population in the United States at this time, but hopefully, similar longitudinal studies as the one previously mentioned will come to reflect a decreasing trend within the newer demographics now affected by food allergy in the years to come.

Sources:

Comments